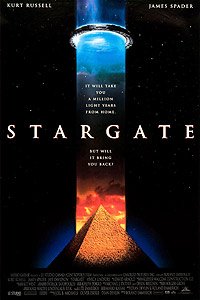

Stargate |

• Directed by: Roland Emmerich. • Starring: Kurt Russell, James Spader, Jaye Davidson, Viveca Lindfors, Alexis Cruz, Mili Avital, Leon Rippy, John Diehl, Carlos Lauchu, Djimon Hounsou, Erick Avari, French Stewart, Gianin Loffler. • Music by: David Arnold. • Directed by: Roland Emmerich. • Starring: Kurt Russell, James Spader, Jaye Davidson, Viveca Lindfors, Alexis Cruz, Mili Avital, Leon Rippy, John Diehl, Carlos Lauchu, Djimon Hounsou, Erick Avari, French Stewart, Gianin Loffler. • Music by: David Arnold.      A small group of US troups and an Egyptologist use an ancient device found in 1920s Egypt to transport themselves to a distant planet. Colonel Jonathan "Jack" O'Neil is sent with some men to explore the unkown but there's only one problem: When they reach this earth-like planet, there is no way to re-open the stargate without the right equipment. They must fight off evil and all to get the stargate back into its "locked" position and save the earth from the deadly bomb which is going to be sent through the stargate by the evil leader... A small group of US troups and an Egyptologist use an ancient device found in 1920s Egypt to transport themselves to a distant planet. Colonel Jonathan "Jack" O'Neil is sent with some men to explore the unkown but there's only one problem: When they reach this earth-like planet, there is no way to re-open the stargate without the right equipment. They must fight off evil and all to get the stargate back into its "locked" position and save the earth from the deadly bomb which is going to be sent through the stargate by the evil leader...

|

Trailers:

| Length: | Languages: | Subtitles: |

Review:

This movie is almost plagiaristically like an episode of the old "Star Trek," in which Kirk and company discover a planetary garden of Eden. In that episode, the inhabitants are simple, have everything they need, know nothing of war or that sex might be evil, and pray to their God, Vaal. On occasion they go to the cave of Vaal and drop off some food obeisance. This seems to make Vaal happy enough to keep these folk in a state of bliss and harmony. Kirk and company don't like this situation, though, because the simple people are clearly "slaves." So, in their wisdom and benevolence, they shoot the Enterprise's phaser banks at the cave of Vaal and wipe it out. Kirk gives the dwellers a little lecture on how they will now learn to make their own decisions and be the happier for it.

You can just see the delayed reactions of these former Eden-dwellers once they realized just what their "liberation" meant: toil, conflict, jealousy, eventually undoubtedly crime, poverty, environmental rape. "Oh, thanks a lot, you guys! Yeah, we were simple but we had a preeeeeeetty good life, and all we had to do was drop off a little fruit. But I guess that a couple of pineapples was too much for you guys! All of a sudden we were 'slaves,' and you had to come along and 'liberate' us. Gee whiz you were only on our planet for three days; did that qualify you as experts in our culture? Did it ever occur to you that maybe we don't want to be like you? But, noooooooooo: you knew what was best for us; you couldn't have us bribing the gods to make things nice for us because this meant we had no 'free will.' You guys are JERKS." Oh, but we have come a long way. Just about any child who's received an iota of cultural awareness education could probably tell you that what Kirk and company did was not particularly sensitive and was more than a bit ethnocentric. This Star Trek episode, after all, came to us forty years ago.

So what is Stargate's excuse?

Toward the end of the movie, the primitive people themselves decide that they can no longer be slaves, and must rise up against their god. As a linguist, I have to wonder where they got this word "slave" from. This is surely a word that would not exist in their language, since all of them, every one, was a "slave" in terms of working for Ra's benefit. The word "slave" would have been synonymous with the word "human." Can you imagine someone on our planet deciding that we had to rise up against "God" and take control of our own lives?

Ra is portrayed as evil in a very human sense: despotic, sadistic, with an angry stare and a nasty temper. This is a being who has lived for thousands of years, traveled through every part of space, is so technologically superior to us that it can bend the laws of physics and accomplish nearly-instant intergalactic travel, and besides all that, started earth's culture. One would think the earthlings might be grateful, or at least curious. It might even seem reasonable that this being would be remarkably wise, well read, and not simply a petty dictator of some primitive desert-dwellers. The very idea that a being such as this would be trying to "cheat death" only to live in a barren castle with almost nothing to do for thousands of years, is a bit strange. But more hackle-raising is that this movie applauds when a mentally disturbed human military colonel in his mid-forties takes it upon himself to kill this ancient, super-intelligent, culture-creating being.

The reasons for Ra's behavior are never questioned, though they may be godly and mysterious. Even the scientist assumes that what Ra is doing must be wrong, but does not say the obvious, "You are thousands of years old, created my civilization, have been to many galaxies. I have so much to learn from you, and certainly have no right to judge your decisions. What's up?"

The cultural arrogance of this movie is not a matter of political correctness. It is a matter of seeing we still believe that everyone should have the same social structure and political beliefs that we have, that we have the right to judge - quickly - and then inflict our will upon creatures who are different from us.

In the most optimistic way, I might suggest that this movie is showing us not general human thinking, but general military thinking. In Stargate, the scientific and cultural discoveries are hidden from the masses by a clearly arrogant military structure, acting on its own without any sort of outside perspective or accountability. The first group sent through the gate was a half dozen grunt soldiers who were clearly incapable, by their training, of an interplanetaryintercultural mission. The colonel's preposterous mission was, "If you see anything that scares you, nuke everything." If the film had been a lampoon of this kind of decision-making, if it had taken a moment's perspective for someone to ask if maybe Ra was smarter than the colonel and if maybe the peasants would be happier mining the mineral for Ra, than in possessing guns and the free will to use them, then the whole precept would have been worth it. Sadly, though, the script does not diverge for one single moment away from its applause of the military actions taken, from the heroism of the humans for destroying the social fabric they entered, from the righteousness of killing the god.

Review by SashaWrites from the Internet Movie Database.

Movie Database